This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, December 2014 (Vol. 83, No. 4), pp. 38–49.

By Laurel S. TerryEditor’s Note: The following article and “Testing Foreign-Trained Applicants in a New York State of Mind” are based on Diane Bosse’s and Laurel S. Terry’s presentations at their joint session “Admitting Foreign-Trained Lawyers: Understanding the Issues” at the 2014 NCBE Annual Bar Admissions Conference held on May 1–4, 2014, in Seattle, Washington. The articles are intended to complement each other by providing a snapshot of the foreign-educated applicant pool taking the New York Bar Examination and the rules by which these applicants may qualify to take the exam, and exploring the broader range of methods by which foreign-educated applicants may be permitted to practice in U.S. jurisdictions, including a discussion of the reasons why jurisdictions should consider rules regarding these methods.

Each year, New York has more foreign-educated applicants sit for its bar examination than all of the other states put together.1 Indeed, New York has more foreign applicants in a year than most states have ever had! As explained elsewhere in this issue, New York’s central position in the global economy was the impetus for its policy decision to allow foreign-educated applicants to sit for its bar exam.2 The New York Bar Exam has become a global credential and an instrument of international commerce.

Given New York City’s unique role in the United States as a global financial center, it might be tempting for other states to conclude that they do not need to concern themselves with issues regarding foreign applicants. These issues may seem complicated, and in a world of finite resources, a jurisdiction might decide that, unlike New York, it has too few foreign applicants to justify spending energy on these issues.

While this reasoning is understandable, there are a number of reasons why it is prudent for all jurisdictions to develop admission policies for foreign applicants. These reasons include (1) the needs of clients and citizens in each state, (2) the accountability that comes from having a system of foreign lawyer regulation, and (3) federal interest in these issues as a result of trade negotiations.

In my view, these three reasons are among the reasons why, in January 2014, the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) adopted a resolution that encourages states “to consider the ‘International Trade in Legal Services and Professional Regulation: A Framework for State Bars Based on the Georgia Experience’ [what the CCJ refers to as a “tool kit”] . . . as a worthy guide for their own state endeavors to meet the challenges of ever-changing legal markets and increasing cross-border law practices.”3

This article explains what that “Toolkit” is, how your state can use the Toolkit to address issues related to foreign lawyers, and why you might conclude—as other states have done—that it would be desirable to adopt regulations that govern the means by which foreign lawyers can assist clients in your state.

The ABA Toolkit: A Valuable Resource for Jurisdictions

The CCJ’s January 2014 Resolution encourages states to use the Toolkit developed by the American Bar Association Task Force on International Trade in Legal Services (ITILS).4 This Toolkit is modeled on the approach to foreign lawyer practice used in Georgia, which has assumed a leadership position in adopting rules to address and regulate the ways in which foreign lawyers may practice in that state. It is available on the ITILS Task Force web page and was designed to help states develop a regulatory regime to proactively confront issues arising from globalization, cross-border legal practice, and lawyer mobility.

In addition to setting forth background information about the globalization issues that prompted Georgia to act and discussing how such issues are experienced in every state, the Toolkit includes recommendations for addressing the impact of globalization and issues related to foreign lawyer regulation. These recommendations, derived from the process followed in Georgia, are set forth in six steps, the first of which is to establish a supervisory committee tasked with reviewing and evaluating a state’s existing regulatory system for foreign lawyers. The Toolkit also includes an appendix with basic reference materials and helpful resources.

Most importantly, the Toolkit encourages states to consider the “foreign lawyer cluster” of rules—that is, rules regarding the five ways by which foreign lawyers might physically practice in a state. These five methods of practice are

- temporary transactional practice (including appearing as counsel in a mediation session or international arbitration held in the United States);

- practice as foreign-licensed in-house counsel;

- permanent practice as a foreign legal consultant;

- temporary in-court appearance—i.e., pro hac vice admission; and

- full licensure as a U.S. lawyer.

The Toolkit provides various examples of these practice methods and reasons why a state might consider rules regarding each method of practice.

Few States Have Adopted—or Even Considered—All Five of the “Foreign Lawyer Cluster”

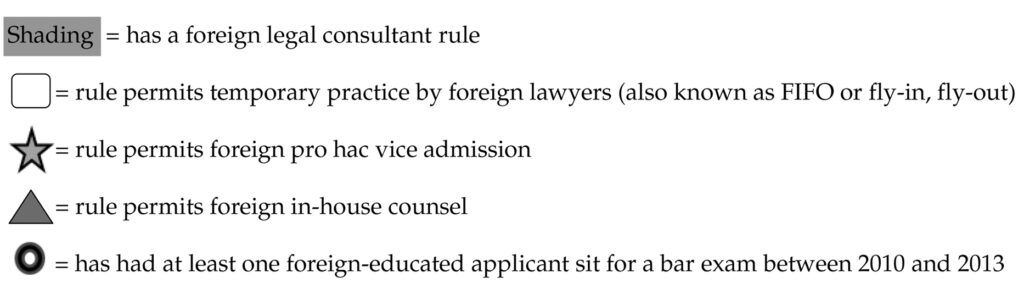

The map and accompanying summary of state foreign lawyer practice rules show how each state stands with respect to adoption of the foreign lawyer cluster of rules.5

Jurisdictions with Rules Regarding Foreign Lawyer Practice (11/14/14)

(Prepared by Professor Laurel Terry on November 14, 2014, based on data from the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility and NCBE.)

As this map shows, only four states—Colorado, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—have policies that address all five of the methods by which foreign lawyers might actively practice in a state—the full cluster. Although a few states have considered and rejected such rules, most states that do not have the full cluster have not publicly rejected these rules—they just seem not to have considered them.6

Because few states have publicly rejected the foreign lawyer practice rules and fewer than 20 states have three or more of these rules, it is logical to assume that in some states, consideration of the full cluster of such rules has simply “fallen through the cracks.” The ABA has model policies that address the first four methods by which foreign lawyers might actively practice in a jurisdiction.7 (The ABA does not have a policy regarding full admission of foreign lawyers.)8 But until the ABA Commission on Ethics 20/20 completed its work in February 2013 (its charge being to perform a thorough review of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct and the U.S. system of lawyer regulation in the context of advances in technology and global legal practice developments), none of these four policies appeared in a rule of professional conduct. Even now, only one of the policies (regarding foreign in-house counsel) appears in such a rule. As a result, the committees charged with reviewing the ethics rules may not have come across any of these policies. Similarly, committees that deal with policies regarding lawyer admission may not have been aware of, or paid particular attention to, the foreign lawyer cluster of model rules, since these model policies do not address the “full admission” issues that occupy most of the time of bar admissions committees. In my view, this may explain why the foreign lawyer cluster may simply have fallen through the cracks.

While the failure to address these issues is understandable, as the CCJ recognized, the time has come for each jurisdiction to consider them. The sections that follow explain some of the factors that your jurisdiction might want to take into account as it considers foreign lawyer admission issues.

Summary of State Foreign Lawyer Practice Rules (11/14/14)

(This document is sometimes referred to as the “Quick Guide” regarding ABA MJP Recommendations 8 & 9, although it also includes information about ABA 20/20 Commission Resolutions #107A–C. It is available at http://tinyurl.com/foreignlawyermap.

There are five methods by which foreign lawyers might actively practice in the United States: (1) through a license that permits only limited practice, known as a foreign legal consultant rule [addressed in MJP Report 201H]; (2) through a rule that permits temporary transactional work by foreign lawyers [addressed in MJP Report 201J]; (3) through a rule that permits foreign lawyers to apply for pro hac vice admission [ABA Resolution #107C (Feb. 2013)]; (4) through a rule that permits foreign lawyers to serve as in-house counsel [ABA Resolutions #107A&B (Feb. 2013)]; and (5) through full admission as a regularly licensed lawyer in a U.S. jurisdiction. (The ABA does not have a policy on Method #5 although there are a number of foreign lawyers admitted annually; information about state full admission rules is available in NCBE’s annual Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements. See alsoNCBE Statistics.)

States that are considering whether to adopt rules regarding these five methods of foreign lawyer admission might want to consider the model provided in International Trade in Legal Services and Professional Regulation: A Framework for State Bars Based on the Georgia Experience (updated January 8, 2014). The Conference of Chief Justices endorsed this “Toolkit” in Resolution 11 adopted January 2014.

| Jurisdictions with FLC Rules | Jurisdictions that Explicitly Permit Foreign Lawyer Temporary Practice | Jurisdiction that Permit Foreign Lawyer Pro Hac Vice Admission | Jurisdiction that Permit Foreign In-House Counsel | Since 2010 has had a foreign-educated full-admission applicant |

| 33 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 32 |

| AK, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE (Rule 55.2), DC, FL, Ga, HI, ID, IL, IN, IA, LA, MI, MN, MO, NH, NJ, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OR, PA, SC, TX, UT, VA, WA | CO, DC (Rule 49(c)(13)), DE (RPC5.5(d)), FL, GA, NH, PA, VA | CO, DC (Rule 49), GA (Rule 4.4), IL, ME (Rule 14), MI, NM, NY, OH (Rule XII), OK (Art. II(5)), OR, PA, TX, UT, VA, WI | AZ, CO (204.2(1)(e)), CT, DE, PA, TX, VA (Part 1A), WA, WI, W | AL, AK, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, FL, GA, HI, IL, IA, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, MO, NV, NH, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WI |

| ABA Model FLC Rule (2006) | ABA Model Rule for Temporary Practice by Foreign Lawyers | ABA Model Pro Hac Vice Rule | ABA Model Rule re Foreign In-House Counsel and Registration Rule | NO ABA policy; Council did not act in Committee Proposal; see state rules |

|

Useful Resource: ABA Commission on Multijurisdictional Practice web page |

Useful Resource: State Rules—Temporary Practice by Foreign Lawyers (ABA Chart) |

Comparison OF ABA Model Rule for Pro Hac Vice Admission with State Versions and Amendments since August 2002 (ABA chart) | In-House Corporate Counsel Registration Rules (ABA chart); Comparison of ABA Model Rule for Registration of In-House Counsel with State Versions (ABA Chart); State-by-State Adoption of Selected ethics 20/20 Commission policies (ABA chart) |

Useful Resource: NCBE Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements |

Note: As the map shows, four states—Colorado, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—have rules for all 5 methods; two jurisdictions have rules on 4 methods (DC and TX); and 13 jurisdictions have rules on 3 methods (AZ, CT, DE, FL, IL, MI, NH, NY, OH, OR, UT, WA, and WI).

(Prepared by Professor Laurel Terry based on implementation information contained in charts prepared by the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility dated 10/7/2014 and 11/14/14, available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/recommendations.authcheckdam.pdf and http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/state_implementation_selected_e20_20_rules.authcheckdam.pdf.)

Editor’s Note: The online version of this Summary of State Foreign Lawyer Practice Rules contains links to the relevant state foreign lawyer practice rules, ABA model rules, and other resources.

Foreign Lawyer Admission: Factors to Consider

Foreign Lawyers Are Relevant to Client and Public Interest

Before a regulator delves into the details of any proposed new rule or policy, it is useful to take a step back and identify the goals that the regulator wants to achieve.9 In my view, the appropriate goals for admissions regulators include client protection, public interest, and access to justice and legal services.10 I believe that a policy that focuses exclusively on the first two of these goals, but excludes the third goal, is incomplete and exposes the entire system to criticism. Thus, a jurisdiction’s consideration of the foreign lawyer cluster should include an analysis of whether its rules have struck the right balance in providing clients and the public with access to legal services.

Your State Likely Has Global Economic Transactions That Involve Foreign Lawyers

It is indisputable that residents of every state live in a world of global commerce. Moreover, the economy of every state in the country would be seriously affected if its citizens were suddenly prohibited from interacting with international buyers, sellers, or tradespeople. For example, every U.S. state except Hawaii exported more than one billion dollars of goods in 2013, and most had 11-figure exports.11 And this is just goods—not services! While probably a number of these billion dollars of sales took place without the assistance of lawyers, there undoubtedly were a number of deals that did require the assistance of both U.S. and foreign lawyers.

If your jurisdiction’s rules prohibit a foreign lawyer from flying to the United States to conduct negotiations or to close a deal, your jurisdiction has just added significant expense to this international transaction and—depending on the sophistication and wealth of the client—may have made it less likely that the deal will happen at all or that it will happen in your state, as opposed to a neighboring state. Thus, the ambiguity that arises from the failure to have the foreign lawyer cluster of rules can have a negative impact not only on clients in your state, but on the public, because the state’s economy may suffer.

Individuals Benefit from Access to Foreign Lawyers

Our history as a nation of immigrants combined with the fact that we live in an era of global travel and the Internet means that individuals, as well as businesses, may need access to foreign lawyers. There undoubtedly are residents of your state who will have interactions with another country that have legal implications, such as an inheritance matter, a family law matter, or a business matter.

Consider a few more statistics. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 20% of married-couple households in the United States have at least one non-native spouse.12 In 1960, approximately two-thirds of U.S. states had a foreign-born population of less than 5%, but by 2010, the numbers were reversed and approximately two-thirds of U.S. states had a foreign-born population greater than 5%.13 Moreover, the jurisdictions that have seen the greatest percentage increase in their foreign-born population are not the ones that you might immediately think of. For example, in Alabama, the District of Columbia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wyoming, more than 25% of their foreign-born population entered the United States between 2005 and 2010.14 Another statistic that shows the interaction between U.S. residents and the rest of the world is the fact that there have been approximately 250,000 foreign-born children adopted by U.S. families between 1999 and 2013.15 Thus, it is likely that individuals within your state, as well as businesses, may need the services of foreign lawyers, as well as U.S. lawyers, at some point in their lives.

U.S. Lawyers Already Engage in Foreign Legal Transactions

What about the U.S. lawyers involved in these foreign transactions? Is this just a “large firm” issue? The data suggest not. Consider, for example, the findings of After the JD II, the second installment of a longitudinal study tracking the careers of a broad cross-section of approximately 4,000 lawyers who graduated from law school in 2000. This second part of the study, conducted in 2007–2008, found that 44% of the surveyed lawyers had done at least some work that involved clients from outside the United States or in cross-border matters. This included two-thirds of lawyers in the largest law firms and 65% of inside counsel. What is even more interesting, however, is that 61% of the surveyed legal services and public defense lawyers had done work that involved non-U.S. clients or non-U.S. law.16 This may be why it is increasingly common for U.S. law firms to engage in practice in a foreign jurisdiction and to include foreign lawyers.

U.S. Law Firms Already Have a Strong Global Presence

In October 2014, in its annual “Global 100” issue, the American Lawyer reported that more than 25,000 lawyers from the AmLaw 200, which are law firms that the American Lawyer has rated among the top 200 according to variables such as size and profits per partner, work in foreign offices in more than 70 countries.17 And in its 2013 Report on the State of the Legal Market, Georgetown Law’s Center for the Study of the Legal Profession reported that 96 global cross-border law firm mergers were announced in 2012 and 56 U.S. law firms opened a new foreign office in 2012.18 If a Global 100 law firm (i.e., one among the top-grossing law firms in the world) has an office in your state, there is a very strong likelihood that one of “your firms” has an overseas office, since 93 of the 100 largest global law firms have offices in more than one country.19

In short, clients in every state are involved in situations in which they might find it useful to have available the services of foreign lawyers. It is in the public interest for these clients to have access to such lawyers in an appropriate, accountable manner.

The Foreign Lawyer Cluster Can Provide Accountability

The Toolkit that the CCJ has endorsed provides a jurisdiction with the opportunity to thoughtfully consider the conditions under which it might want to allow certain kinds of foreign lawyer practice. Given the trade statistics cited above, it seems inevitable that foreign lawyers are interacting with the residents of every state, regardless of whether the state has adopted any of the rules in the foreign lawyer cluster. If a jurisdiction has adopted a policy regarding each of these methods of practice, however, it will be clearer what is—and is not—acceptable behavior. In addition, rules can set forth the consequences of their violation and thus create a system of accountability.

For example, only eight jurisdictions have expressly recognized the right of foreign lawyers to engage in temporary transactional practice in the United States.20 I am sure, however, that there are many more than eight jurisdictions in which foreign lawyers have flown into the United States to negotiate or close a deal. Isn’t it better for a state to have a rule that explicitly addresses this situation and makes it clear, for example, that such practice must be temporary and that the lawyer must not have a systematic and continuous presence in the state? In my view, this kind of temporary transactional practice, which is also known as “fly-in, fly-out” or “FIFO” practice, presents significantly fewer client protection issues than full admission, because the types of clients who use foreign lawyer FIFO services are not likely to be among the most vulnerable U.S. clients. This is because business clients engaged in multinational transactions are more likely to need FIFO legal services than are individual clients. Thus, I find it illogical that in 2013, 28 states permitted a foreign-educated applicant to sit for a bar exam,21 which provides full admission and arguably raises greater client protection concerns, but only 8 jurisdictions currently have a rule regarding temporary FIFO practice by foreign lawyers, and only 14 states currently have a rule that permits foreign in-house counsel.22

As noted below, this issue of temporary practice by foreign lawyers has come up in the context of the ongoing United States–European Union (US-EU) trade negotiations. While temporary practice is not an issue that bar examiners have traditionally considered, it is one of several methods by which foreign lawyers might practice in a jurisdiction and is thus an admission issue. Accordingly, I believe it would make sense for the admissions community to make sure that its jurisdiction addresses the entire foreign lawyer cluster. The Toolkit can provide guidance on how a jurisdiction might convene and structure these discussions.

Some of the Foreign Lawyer Cluster Is Under Discussion in the US-EU “T-TIP” Trade Negotiations

As I mentioned above, the concept of foreign lawyer temporary practice has been the subject of discussion in the ongoing US-EU trade negotiations. The formal name of these negotiations, which were launched in 2013, is the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, but they are usually referred to as T-TIP.

The T-TIP negotiations were featured at one of the education program sessions at the January 2014 CCJ meeting. The U.S. position was presented by Thomas Fine, who is Director of Services and Investment at the Office of the United States Trade Representative. The European position was presented by Jonathan Goldsmith, who is Secretary General of the Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe, which is known as the CCBE.23 Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman from New York moderated this panel, on which I also participated.

This session provided U.S. and EU lawyer regulators with the opportunity to speak directly to one another. Jonathan Goldsmith began by noting that T-TIP is potentially the biggest bilateral trade deal in the world, that it aims to remove trade barriers between the European Union and the United States in a wide range of sectors, and that independent research has shown that it could boost the European Union’s economy by €120 billion, the U.S. economy by €90 billion, and the economy of the rest of the world by €100 billion. He discussed the importance of collaboration between the CCBE and the CCJ (and between the CCBE and the ABA). He emphasized that if those who regulate U.S. and EU lawyers can come to an understanding amongst themselves, then it makes it much less likely that their respective governments will enter into trade agreements that the legal profession or its regulators would find problematic.

The CCBE’s T-TIP “Requests” Are Consistent with ABA Policy

The CCBE has developed T-TIP “requests” that it has presented to the CCJ and to the ABA.24 In the context of trade negotiations, a country’s “offer” indicates the changes that it is prepared to make, and its “requests” state the changes that a country would like its trading partner to implement. Although governments are the only entities that have the official power to issue requests or offers, the CCBE developed a set of requests in order to stimulate discussion among the U.S. and EU legal professions and their regulators. The CCBE’s requests to the CCJ and the ABA are as follows:

A Lawyer with a title from any EU member state must be able to undertake the following activities in all U.S. states, without running the risk of illegal

practice of law:

- Temporary provision of services under home title in home law, EU law, international law, and third country law in which they are qualified, without a local presence;

- Establishment (i.e. with local presence) under home title to provide services in home law, EU law, international law, and third country law in which they are qualified;

- International Arbitration (as counsel or arbitrator);

- International Mediation (as counsel or mediator);

- Partnership under home title with US lawyers (with local presence);

- Employment of US lawyers (with local presence) (i.e. no restrictions on structures for establishment, for instance requirements to have a local lawyer as partner, or preventing a local lawyer being an employee).25

All of the CCBE’s requests are consistent with existing ABA policy, with the exception of the CCBE requests regarding lawyers who serve as “neutrals” (i.e., as arbitrators and mediators). The ABA does not have a policy on this topic because, in the United States, nonlawyers are allowed to serve as mediators and arbitrators. The CCBE’s requests address two of the five methods in the foreign lawyer cluster—temporary practice (which the ABA, in its Model Rule for Temporary Practice by Foreign Lawyers, defines to include both transactional work and representing clients in mediation and arbitration) and practice as a foreign legal consultant. Although the CCBE’s last two requests might have been worded more clearly, based on my knowledge of the field and statements that I have heard from CCBE representatives, I believe that the last two requests address what is often referred to as “association” rights—that is, the right of a foreign law firm to open a law firm office in a U.S. state and to have that law firm office staffed by a state-licensed lawyer who is an employee of the law firm, rather than a partner. (Some countries require the locally licensed lawyer to be a partner.) The CCBE requests also ask for the ability of a foreign lawyer who is either located outside of the United States or properly practicing within the United States to have as a partner a U.S. lawyer who practices in a U.S. state in which he or she is licensed. (Not all countries permit this type of international law firm partnership.) If I am correct regarding the meaning of the CCBE’s last two requests, then ABA policy is consistent with the CCBE’s requests that a foreign lawyer or law firm should be able to have a U.S. lawyer as a partner or as an employee, provided that the U.S. lawyer and the foreign lawyer are properly licensed in the jurisdiction in which each one practices.26

The Nature of the Discussions About the CCBE’s T-TIP Requests

There are several noteworthy aspects of the CCBE’s requests to the U.S. legal profession. First, the requests seek a U.S. commitment that covers “all US states.” During a US-EU Summit held in August 2014 during the ABA Annual Meeting, CCBE officials acknowledged the state-based nature of U.S. lawyer regulation and the U.S. constitutional structure but expressed frustration with the piecemeal state of U.S. lawyer regulation. They emphasized that they have sought a commitment from “all US states.” My impression of the Summit was that the Europeans expressed a higher level of frustration with the U.S. federalism situation than I have heard in recent years.

Second, with the exception of lawyers who serve as neutrals, the subjects addressed in the CCBE’s requests are also covered in the foreign lawyer cluster presented in the Toolkit, which the CCJ has commended to states’ attention.

Third, the CCBE has presented data to the ABA regarding perceived deficits in the foreign lawyer rules in a number of U.S. jurisdictions. The map in this article was inspired by a chart that the CCBE presented to the ABA in 2013 that listed every U.S. jurisdiction and rated each U.S. state as “green” (yes) or “red” (no) on nine issues related to a foreign lawyer’s ability to practice in the United States or the ability of a foreign law firm to hire a properly licensed U.S. lawyer. The CCBE’s green-red chart was based on preliminary data from an International Bar Association (IBA) survey that recently was publicly released.27 The survey, designed to evaluate ease of international trade in legal services, covers jurisdictions from around the world, including all 50 U.S. states, and addresses a number of issues related to the ability of foreign lawyers or firms to assist their clients. The IBA survey is likely to be influential in the T-TIP negotiations and elsewhere. Governments and negotiators around the world already have begun to examine its data.28

How U.S. Jurisdictions Might Proceed in the Context of the T-TIP Negotiations

In my view, neither the T-TIP negotiations nor the CCBE’s requests should drive U.S. policy.29 Instead, U.S. states should consider their regulatory objectives and then adopt rules and policies that advance those objectives. The T-TIP negotiations do, however, highlight important issues that I believe regulators have an independent obligation to consider. Given the impact of globalization on every U.S. jurisdiction, regulators are doing clients and the public a disservice if they fail to consider the entire foreign lawyer cluster of rules. The underlying data on which the map is based suggest that many jurisdictions have not yet taken the opportunity to consider the entire foreign lawyer cluster of rules. Perhaps the T-TIP negotiations will provide jurisdictions with the “nudge” they need in order to consider these issues. As they do so, the Toolkit can provide them with useful resources and advice.

It is important for each jurisdiction to consider these issues. If I were asked for my advice about the optimal outcome, I would recommend that states adopt a rule for each of the five methods by which lawyers might actively practice in a jurisdiction. I would also recommend that jurisdictions consider the “association” rights of U.S. lawyers. I believe that (1) globalization is here to stay; (2) foreign lawyers are present in all U.S. jurisdictions, regardless of whether a jurisdiction has adopted any rules regarding their practice; and (3) it is important for the regulatory systems in jurisdictions to consider client needs and public interest, as well as client protection. I would also state my belief that the client protection and public interest concerns are fewer and different when one considers limited practice by foreign lawyers rather than full admission.

While the T-TIP negotiations do not and should not require that a jurisdiction take action, I do not believe that jurisdictions should refuse to act simply because they wish that legal services were not the subject of trade negotiations. Jurisdictions should instead recognize the reality of globalization that the T-TIP negotiations represent and consider whether and how they should adopt rules that regulate the ways in which foreign lawyers can practice in their jurisdiction.

Conclusion

New York, despite its high concentration of foreign applicants, is not the only state whose citizens engage with foreign nationals and need lawyers trained to deal with legal issues that cross international borders. Because each state (except Hawaii) exports over one billion dollars of goods annually,30 and because of the other globalization attributes cited earlier in this article,31 the citizens and businesses in each state undoubtedly will need to have available on at least some occasions the services of foreign lawyers.

It is in the interests of clients and the public for jurisdictions to consider the foreign lawyer cluster, which includes not only full admission, but other mechanisms by which foreign-trained lawyers can practice on a limited scale in the United States, including pro hac vice admission, temporary practice, serving as in-house counsel (which requires registration in some states), and admission as a foreign legal consultant. Rules permitting such limited practice merit consideration, whether or not full admission is available to the candidate educated outside the United States. And even though it may not have been traditional for the admissions community to consider the foreign lawyer cluster, I would urge this community and state Supreme Courts to make sure that some entity is examining these issues and that these issues do not fall through the cracks. Isn’t it better for states to consider thoughtfully and reflectively, rather than reflexively in the middle of a crisis, the conditions under which they want to permit foreign lawyers to practice within their borders?

Notes

- See Laurel Terry, Summary of Statistics of Bar Exam Applicants Educated Outside the US: 1992–2013 (It’s Not Just About New York and California) (updated April 4, 2014), available at http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/l/s/lst3/Summary_%20of_Applicants_%20educated_%20Outside_US_1992-2013.pdf. (Go back)

- Diane F. Bosse, “Testing Foreign-Trained Applicants in a New York State of Mind,” 83(4) The Bar Examiner 31–37 (December 2014). (Go back)

- Conference of Chief Justices, Resolution 11: In Support of the Framework Created by the State Bar of Georgia and the Georgia Supreme Court to Address Issues Arising from Legal Market Globalization and Cross-Border Legal Practice (Jan. 29, 2014), available at http://ccj.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/CCJ/Resolutions/01292014-Support-Framework-Created-State-Bar-Georgia.ashx. (Go back)

- American Bar Association Task Force on International Trade in Legal Services, International Trade in Legal Services and Professional Regulation: A Framework for State Bars Based on the Georgia Experience (updated Jan. 8, 2014). (Go back)

- I prepared the original version of this map, dated January 6, 2014, for the January 2014 meeting of the Conference of Chief Justices. I have since updated the map several times, and the most recent version, along with the one-page summary document that includes links to the relevant state foreign lawyer practice rules, ABA model rules, and other resources, is available on the ABA website at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/mjp_8_9_status_chart.authcheckdam.pdf and on my personal website at http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/l/s/lst3/Laurel_Terry_map_foreign_Lawyer_policies.pdf. (Go back)

- See American Bar Association, State Implementation of ABA MJP Policies (Oct. 7, 2014), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/recommendations.authcheckdam.pdf; American Bar Association Center for Professional Responsibility Policy Implementation Committee, State by State Adoption of Selected Ethics 20/20 Commission Policies and Guidelines for an International Regulatory Information Exchange (Nov. 17, 2014), available at

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/professional_responsibility/state_implementation_selected_e20_20_rules.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back) - These four ABA policies are (1) the Model Rule for the Licensing and Practice of Foreign Legal Consultants, (2) the Model Rule for Temporary Practice by Foreign Lawyers, (3) the Model Rule on Pro Hac Vice Admission, available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/ethics_2020/2013_hod_midyear_meeting_107c_redline_with_floor_amendment.authcheckdam.pdf; and (4) the Model Rule of Professional Conduct 5.5 (Unauthorized Practice of Law; Multijurisdictional Practice of Law) and the Model Rule for Registration of In-House Counsel, available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/ethics_2020/20130201_revised_resolution_107a_resolution_only_redline.authcheckdam.pdf and http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/ethics_2020/20130201_revised_resolution_107b_resolution_only_redline.authcheckdam.pdf. (Go back)

- In 2011, the Special Committee on International Issues of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar developed a recommendation for full admission of foreign lawyers who, inter alia, completed a proposed LL.M. degree, but the Council did not take any further action. See Laurel S. Terry, “Transnational Legal Practice (United States) [2010–2012],” 47 Int’l Law. 499, at 504–506 (2013) (discussing the 2011 report recommending to the Council a Proposed Model Rule on Admission of Foreign Educated Lawyers and Proposed Criteria for ABA Certification of an LL.M. Degree for the Practice of Law in the United States). As the article explains, the Council took no action on this recommendation. (The report is available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/council_reports_and_resolutions/20110420_model_rule_and_criteria_foreign_lawyers.authcheckdam.pdf.) (Go back)

- See Laurel S. Terry, “Why Your Jurisdiction Should Consider Jumping on the Regulatory Objectives Bandwagon,” 22(1) Prof. Law. 28 (Dec. 2013). This is a short version of an article I cowrote with Australian regulators Steve Mark and Tahlia Gordon. (Go back)

- Id. at 5. (Go back)

- See U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 2013 NAICS Total All Merchandise Exports to World, http://tse.export.gov/TSE/TSEHome.aspx. (Select “State Export Data,” then “State-by-State Exports to a Selected Market,” with “World” in the drop-down menu.) (Go back)

- See U.S. Census Bureau, “Census Bureau Reports 21 Percent of Married-Couple Households Have at Least One Foreign-Born Spouse,” Release Number: CB13-157 (Sept. 5, 2013), https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2013/cb13-157.html# (last visited Nov. 1, 2014). (Go back)

- See U.S. Census Bureau, “America’s Foreign Born in the Last 50 Years” at 3, available at http://www.census.gov/how/pdf/Foreign-Born–50-Years-Growth.pdf. (Go back)

- See U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey Briefs, The Newly Arrived Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 2010” at 6. (Go back)

- U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Intercountry Adoption, Statistics, http://travel.state.gov/content/adoptionsabroad/en/about-us/statistics.html (showing 249,694 adoptions between 1999 and 2013) (last visited Nov. 1, 2014). I would like to thank Theresa Kaiser for calling my attention to this statistic. See Theresa Kaiser, “Globalization and the Transformation of Legal Practice: Implications for JD Legal Education,” American University Washington College of Law, Office of Global Opportunities, Global Presentations Paper 1 (2014), available at http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/go_global/1. (Go back)

- American Bar Foundation & NALP Foundation for Law Career Research and Education, After the JD II: Second Results from a National Study of Legal Careers 35 (2009). The nationally representative sample of lawyers consisted of new lawyers from 18 legal markets, including the 4 largest markets (New York City, the District of Columbia, Chicago, and Los Angeles) and 14 other areas consisting of smaller metropolitan areas or entire states. (Go back)

- See “Outward Bound,” American Lawyer 67 (Oct. 2014, the Global 100 issue). (Go back)

- Georgetown Law, Center for the Study of the Legal Profession, 2013 Report of the State of the Legal Market at 8. (The 2014 Report did not contain similar information about globalization.) (Go back)

- See “Outward Bound,” supra note 17, at 108–110. (Go back)

- Supra note 5. (Go back)

- Supra note 1. (Go back)

- Supra note 5. (Go back)

- The CCBE represents the bars and law societies of 32 member countries and 13 further associate and observer countries, and through them more than one million European lawyers. Most of these bars and law societies serve as regulators within their jurisdictions. Founded in 1960, the CCBE is recognized as the voice of the European legal profession by the EU institutions and acts as the liaison between the EU and Europe’s national bars and law societies. (Go back)

- The author has personal knowledge of the following facts: The CCBE has transmitted its requests in writing to the ABA President. They were also discussed at the US-EU Summit held in August 2014 during the ABA Annual Meeting. The ABA has responded to the CCBE’s requests by noting that changes must be made on a state-by-state basis, in light of the U.S. system of state-based judicial regulation, which the ABA supports. It also noted that the only topic addressed in the CCBE requests for which the ABA does not have a policy position is the issue of lawyers who serve as neutrals in mediation or arbitration, as opposed to representing clients. The CCBE presented a draft of its requests to the CCJ in January 2014. After the CCBE formally adopted its requests, it subsequently transmitted them to the CCJ. (Go back)

- Council of Bars and Law Societies of Europe, “CCBE request to the United States in the context of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations,” available at http://www.ccbe.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/NTCdocument/European_Legal_Profe1_1415787235.pdf. (Go back)

- See supra note 7 for links to the ABA’s policies addressing the methods by which foreign lawyers might actively practice in a jurisdiction. The ABA has not adopted any policy about lawyers who serve as neutrals because, in the United States, serving as a neutral is not an activity that is “reserved” to lawyers, and therefore it is not covered by Unauthorized Practice of Law provisions. The CCBE has stated that it wants “off the [negotiating] table” the issues of foreign in-house counsel, foreign pro hac vice, and full admission of foreign lawyers (the other three of the five methods in the foreign lawyer cluster). The CCBE also stated that it wants off the table “[a]ccess to the EU laws on free movement of lawyers (Services Directive 77/249/EEC and Establishment Directive 98/5/EC),” both of which limit the EU’s lawyer mobility rules to European lawyers who are citizens of an EU member state. Thus, a U.S. citizen who is a properly licensed EU lawyer cannot take advantage of the EU lawyer mobility directives that allow a lawyer in one EU member state to practice on a temporary or permanent basis in another EU member state. Citizenship requirements can be controversial, and many governments raise these types of barriers in trade discussions. In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional a citizenship requirement for lawyers. See In Re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717 (1973) (a Connecticut rule that prohibited an otherwise qualified Netherlands citizen from taking its bar exam was held to unconstitutionally discriminate against a resident alien). The ABA has not formally adopted a position regarding the citizenship requirements found in the EU Directives. (Go back)

- The CCBE green-red chart was based on data found in a draft of the IBA survey, the final version of which has now been released. See International Bar Association, International Trade in Legal Services, http://www.ibanet.org/PPID/Constituent/Bar_Issues_Commission/BIC_ITILS_Map.aspx (last visited Nov. 8, 2014). Results for U.S. jurisdictions can be accessed by selecting “Americas” under “Regions,” with the option of selecting a specific “Ease of Trade” category. Clicking on a specific jurisdiction will reveal the list of survey questions and the jurisdiction’s responses. Because this data is likely to be influential, I recommend that jurisdictions review their information on this web page for accuracy and contact the ABA Task Force on International Trade in Legal Services (or me) to report any inaccuracies so that this information can be conveyed to the IBA. It is not clear, however, whether or when the data will be updated. (If jurisdictions would prefer to review the data in pdf format, they can access the entire 700+ page report, IBA Global Regulation and Trade in Legal Services Report 2014, at http://www.ibanet.org/Document/Default.aspx?DocumentUid=1D3D3E81-472A-40E5-9D9D-68EB5F71A702. The U.S. data begins on page 493.) (Go back)

- E-mail from Thomas Fine, Director of Services and Investment, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, to the author (Nov. 12, 2014) (“The IBA survey has been circulated to all governments participating in the Trade in Services Agreement negotiations in Geneva, including the US and the EU. It provides a sound factual basis for further discussion of legal services.”) (Go back)

- It is worth noting, however, that if U.S. states fail to take action that acknowledges and responds to the global situation in which U.S. citizens find themselves, there may be increasing pressure from numerous sources to nationalize U.S. lawyer regulation—which is the implicit threat that underlies the CCBE’s requests. (Go back)

- Supra note 11. (Go back)

- Supra notes 11–16. (Go back)

Laurel S. Terry is the Harvey A. Feldman Distinguished Faculty Scholar and Professor of Law at Penn State’s Dickinson Law, which is one of two ABA-accredited Penn State law schools. She writes and teaches about legal ethics and the international and interjurisdictional regulation of the legal profession and is active in international, national, and state organizations that address lawyer regulation issues. Her service has included participating on committees that address all three stages of lawyer regulation: admissions, conduct rules, and discipline. Terry was educated at the University of California San Diego and the UCLA School of Law. Before her academic career, she clerked for the Hon. Ted Goodwin of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and worked in the litigation department of a large law firm in Portland, Oregon.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.

[apss_share]